Huh & Sejnowski (2018) - Gradient Descent for Spiking Neural Networks

25 Jun 20212. Motivation

3. Main Contribution

4. Previous Attempts to Supervised Learning in SNNs

5. Methods

6. Results

You can find the paper here.

Why am I reading this paper?

I came across this one while researching stochastic vs batch training for SNN. My aim is to better understand how to accumulate the gradients and whether there is a prominent difference between accumulating the gradients in a rate-based networks (ANNs) vs. spiking nets.

Motivation

One of the main limitations of SNN is that we don’t know how to train them and therefore we are unable to reap the benefits of spike-based computations.

ANNs can be seen as a sub-category of SNN. In fact, a SNN can be reduced to a rate-based network in the “high firing-rate limit” (quoting the authors).

One interesting question that was brought up in the paper is what kind of computation can we unlock if we manage to train SNN? What kind of computation becomes possible then?

Main Contribution

A novel approach for training SNN that is not subjected to specific neuron models, network architecture, loss functions or, a particular task, one that is revolving around the formulation of a differentiable SNN for which the gradient can be derived.

Note: The goal is not to have a biologically-plausible learning rule but to derive an efficient learning method. Once SNN networks are trained, we can then try to analyze this Pandora’s box to reveal computational processes of the brain or come up with other algorithms that are hardware-friendly.

Previous Attempts to Supervised Learning in SNNs

- Spike Response Models can simulate SNN dynamics without the need for integration. They rely on impulse response kernels to describe the network behavior.

- As SRM relies on the spike times (the state variables of SNNs), accurately calculating the derivatives of these spike times to obtain an update rule becomes challenging (simply because they are not differentiable :D ).

- SpikeProp -“Error-backpropagation in temporally encoded networks of spiking neurons”, (2002) can be used to train feedforward networks of neurons firing a single spike. Other variants extended the algorithm to allow for multiple spikes for the input and hidden layers yet only the first output spike is considered for error propagation.

- Other algorithms that seem to work with variable spike counts have shorcomings as well:

- Can train only an output/readout layer where a desired target output pattern can be supplied.

- Usually the learning rules suggested are neuron models-agnostic.

- Loss functions used penalize the error between a desired and target spike trains which in practice is not frequently available.

-

Biologically-plausible rules that are based on Hebb’s postulate combining Hebbian learning and gradient descent such as STDP (ex. ReSuMe - “Supervised learning in spiking neural networks with resume:sequence learning, classification, and spike shifting” , (2010)) and reward-modulated STDP do not in general guarantee convergence? (not sure what to think about that though 😅)

- Converting trained ANN models into spiking models do not help explore new computational solutions that utilized spike times. These are approaches are therefore limited in that sense.

Methods

A differentiable formulation of SNN

- In this paper, the authors rely on synaptic current dynamics.

- By using a differentiable current synapse model, the authors seem to get away from the non-differentiability problem of SNNs. The right question at this point is how do they do that? :)

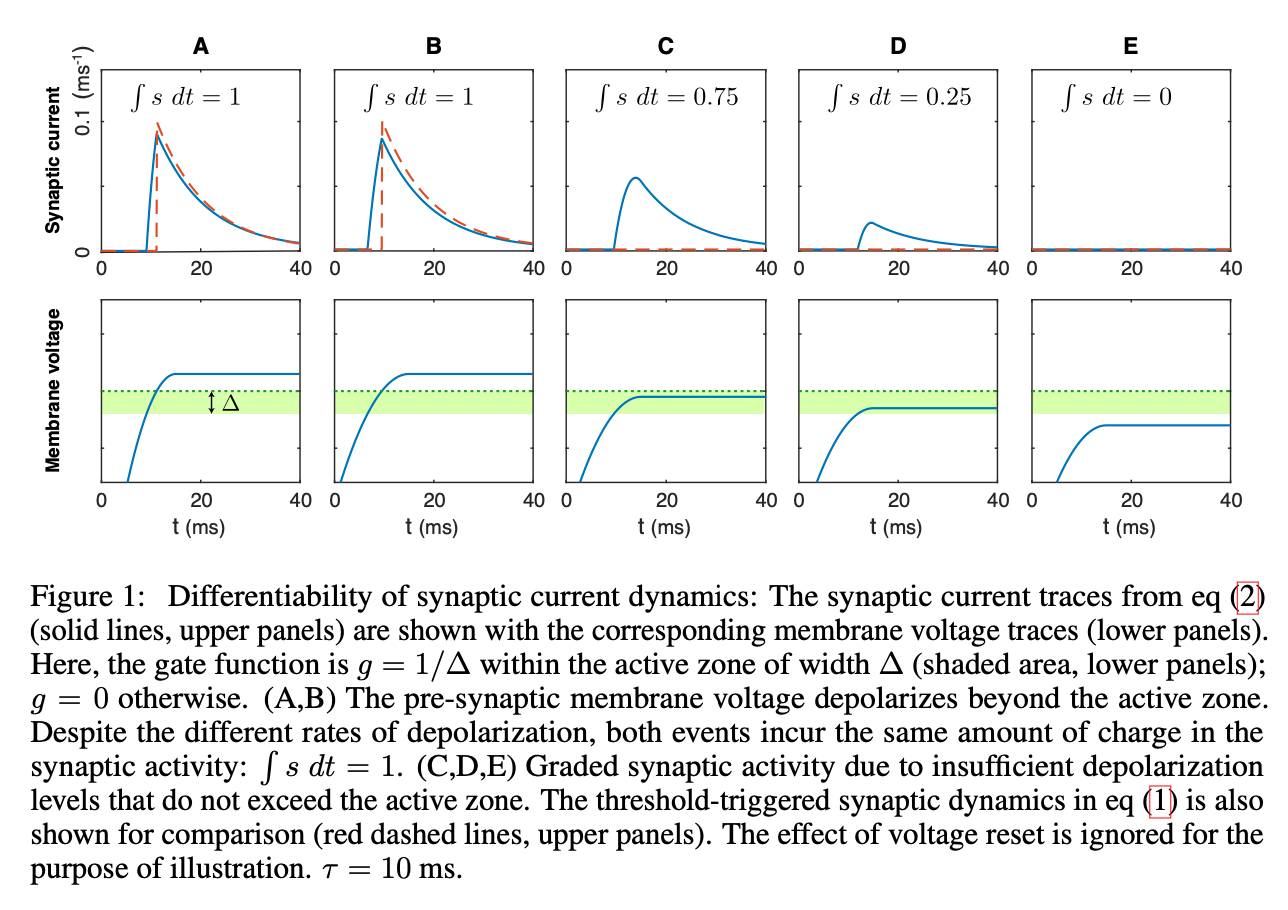

Most models describe the synaptic current dynamics as linear filter process which instantly activates when the presynaptic membrane voltage $v$ crosses a threshold.

-

This means that unless the membrane voltage crosses the threshold, we don’t get a synaptic response, so an all-or-none response.

-

What is done differently in this paper is that they replace this threshold function with a non-negative gate function. This minor twist is quite helpful as it makes the synaptic current response change gradually throughout what they refer to as a small active zone, or area around the threshold (as opposed to a hard threshold). In other words, when the membrane voltage falls within this region, the synaptic current strength changes non-abruptly.

-

We can summarize the cases hence as:

- Within the active zone, the membrane votage induces a graded synaptic response.

- Beyond this small region, the post-synaptic potential has a constant charge (area under the curve).

- Below the active zone, no synaptic response is generated.

which is equivalent to a soft-clipping function.

Define an entire network around this new formulation

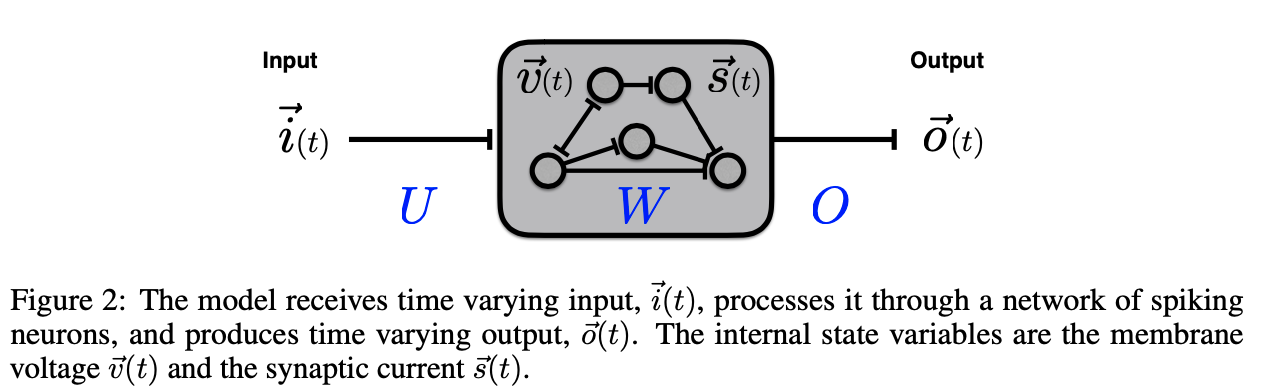

Now that we have a differentiable synaptic current model, we can formulate the network input-output dynamics around it.

- Network input: defined by the input current vector, $\vec{i }$.

- Network state: is fully described by the membrane voltage and current, $\vec{v(t)}$, $\vec{s(t)}$.

- Network output: defined as linear readout of the synaptic current, $\vec{s(t)}$.

Next step is to optimize the weight matrices for the input layer, recurrent connections and readout, $U$ , $W$ and $O$ which can now be accomplished by gradient descent.

Gradient Descent

Without going through all the math (partly because I don’t like equations that much and, I don’t fully grasp them for now 🙈), the weight matrices optimization problem is accomplished through backpropagation dynamics of adjoint state variables or the Pontryagin’s minimum principle.

At the end, we get a formula for the gradient that resembles the reward-modulated STDP; a presynaptic input is multiplied by a postsynaptic spike activity and a temporal error signal.

Results

This approach is tested on a predictive coding task (i.e matching (reproducing) input-output behavior also auto-encoding task) and delayed-memory XOR task where the XOR operation is performed on the historical input which is stored.

The latter task is used to demonstrate the ability of the algorithm to train an SNN performing a non-linear computations over larger timescales (> time constants).